Originally posted by Allison D. Reid:

Many writers struggle with dialogue, maybe because there is so much pressure to get it right. Speaking in someone else’s voice isn’t always easy, yet as writers we end up with a whole cast of characters who all need distinct, unique voices, and it is up to us to provide them. Who would want to read a book where all the characters sound the same? Boring…and confusing.

But creating our characters’ voices is only the beginning—they still need something authentic and interesting to say, not to mention the writing itself must have all the correct grammar and punctuation.

I thought this week I might share some tips for writing dialogue, and anyone who wants to add their own in the comments section is welcome. No, I am not an expert. These are based on my own experience as a writer/editor, and on advice I have received from others over the years. I am still learning and improving, and frequently need to go through and re-examine my own dialogue when I am editing.

TIP 1 – FINDING YOUR CHARACTER’S VOICE.

As I mentioned earlier, the last thing you want is for all of your characters to sound the same. Even people growing up in the same household will vary in their speech patterns. An outgoing person might have the tendency to talk a lot, while a more reserved person may say very little at all. Knowing your characters well is vital to writing good dialogue. What are their personalities and thought processes? What would they say, and how would they say it? Would they use big words or simple ones, formal speech or slang? Does she talk faster when excited? Does he deliberate over every word? Do they live in a region with a dialect? All things to consider. A good test is to strip away the identifiers in a section of dialogue. Can you still tell who is speaking, just from the way the words are spoken?

TIP 2 – HOW MUCH REALISM IS NECESSARY?

I took a writing class once where we had an unusual assignment to help us learn about dialogue; go sit in a public place and listen in on the surrounding conversations. We were supposed to return with our observations about how people naturally speak to each other. Several things stood out for me.

- People rarely give direct, simple answers to a question. They tend to dance around it and give explanations rather than just say yes or no.

- They easily tangent from subject to subject, sometimes having multiple conversations simultaneously. They might eventually circle back to the original topic, or never resolve it at all.

- There tend to be lots of extra pauses, ummm’s, uh’s, like’s, and external interruptions.

Does all of this really belong in a story? Probably not, especially the latter two.

While the point of that assignment might have been learning how to re-create realistic conversation, I think for me it was a lesson in how not to write dialogue. When it comes to what our characters do, we don’t think twice about skipping over all the mundane parts of the daily routine. No one wants to follow their characters to the bathroom ten times a day, or watch them cruise around the grocery store checking package labels—unless there is a point to doing so. Why should dialogue be any different? If it does not enhance our character’s development or further the plot in some way, it doesn’t belong. Make every spoken word count so that it has purpose and meaning, otherwise it is just taking up valuable real estate.

TIP 3 – WHAT ABOUT SPECIAL SPEECH?

Regional dialects, “thee and thou,” historical, and traditional fantasy dialogue are all under this category. My advice is to proceed carefully. It is usually better to give the occasional flavor of a dialect than try to replicate the whole thing, especially if you do not speak in that dialect yourself. It won’t sound authentic, and you’re bound to make mistakes. Writing in dialect can get very tedious for the writer and hard to understand for the reader. Choosing a selection of words that will make it obvious where the speaker is from, and using them consistently, can be quite effective.

Thee and thou I wouldn’t use at all in a long piece, unless you know you can authentically pull it off and the story absolutely needs it. Most writers don’t get the grammar right consistently and it just doesn’t work. Readers also tire of it pretty quickly.

Historic and fantasy-specific language is pretty well accepted. Readers of these genres are quite comfortable with the tradition and actually expect the use of older words and more formal, elegant speech.

What they are not as likely to forgive is language that will pull them out of whatever era they have settled into. Don’t use modern sounding words, or worse yet, metaphors or sayings that refer to things that would not have even existed yet. This is where an online dictionary can be your best friend. Yes, you already know what a given word means, but scroll down to see the word’s origin, or etymology. You can find out where the word came from, and when it came into use. If you’re writing a medieval era story for example, don’t use words that didn’t come into use until the 1700’s or later. It will greatly annoy your more savvy readers and make you look like an amateur.

TIP 4 – WHAT COMES AFTER THE QUOTE?

One of the most difficult parts of writing dialogue can be knowing what to say after the quotation marks are closed. There are lots of different opinions out there, and I can’t say that I agree with all of them. He said, she said—pretty standard. Some advocate that you shouldn’t use much else, that the reader will just tune it out after a while and focus only on the dialogue itself. Others say varying it up strengthens the writing; he stated, she replied, they inquired, etc.

Both camps are pretty adamant, but I think this is one of those areas where writers have some leeway. Neither is technically right or wrong—it is just a matter of personal taste and writing style. I tend to vary it up because as a writer I get bored with just he said, she said. And sometimes including some extra descriptive words (yes, even those controversial words ending in “ly”) help me convey the emotions and facial expressions of the speaker.

That being said, be careful of ending your dialogue with phrases like, he laughed. Try to laugh an entire sentence sometime and let me know how that works out. It is more correct to say something like, he said as he laughed. The difference may seem subtle, but grammatically there is a difference. Also, be aware of whether your character is making a statement or asking a question. If there is a question mark at the end of the sentence, use he asked rather than he said, and vice versa.

TIP 5 – COMMAS, AND PERIODS, AND QUOTATION MARKS, OH MY!

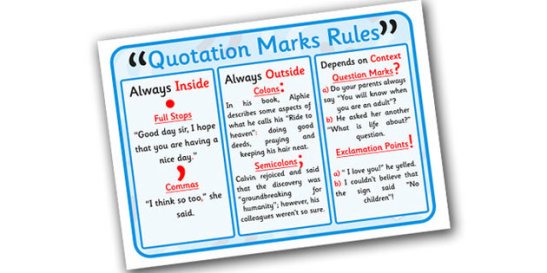

Yeah, this is grammar, and I’m sorry. But as an editor, it makes me crazy when writers don’t know how to correctly punctuate their dialogue. If you are an American writer, please keep your periods and commas inside the quotation marks. “Yep, just like this,” she said. “Not like this”. Also note that I did not write, “Yep, just like this.” She said. She said is not a sentence by itself.

If someone in your story is speaking for a long time, requiring more than one paragraph of dialogue, do not end each paragraph with closing quotation marks. However, every time you start a new paragraph, begin it with quotation marks. The reader will understand your character is still speaking. Reserve your ending quotation marks for the end of the very last paragraph of the dialogue.

Quotation marks can also be confusing when someone who is already speaking quotes another person. For instance, “My grandmother always used to say, ‘cheaters never win, and winners never cheat.’” The regular double quotes are for the person speaking, while the information being quoted is enclosed in single quotation marks. Make sure that you have both beginning and ending quotation marks for each.

Quotation marks should be reserved for spoken words only. Inner thoughts written as dialogue should always be in italics. That guy is crazy, she thought.

Lastly, check to make sure all your quotation marks face the right way. When typing things for the first time, your word processing program will position them correctly. But once you start editing, cutting, pasting, inserting, and moving text around, sometimes they can get turned the wrong way. It is easy not to notice unless you are looking, so make this part of your self-editing process. It is way easier to fix these issues as you go, rather than having to find and correct them in an entire manuscript after the fact.

THESE ARE JUST A FEW OF MY THOUGHTS ON WRITING DIALOGUE. WHAT MAKES GOOD DIALOGUE FOR YOU AS A WRITER OR READER? WHAT MAKES THE STORY STRONGER, AND WHAT MAKES YOU WANT TO STOP READING? HOW CAN YOU LET WHAT OTHERS HAVE DONE INFORM YOUR OWN WRITING TO MAKE IT BETTER?

No comments:

Post a Comment