I came from a family of storytellers, I mean, gifted storytellers. They could pick you up and lift you into a tale like none other I have ever known. I apprenticed under them, and it made me the writer I am. I have been telling stories all my life and writing for most of my life, and at first, the storytelling didn’t translate to the written word.

If I wrote the story as I heard it, it always fell flat. There was no way to transfer the experience of telling a story to writing one. The teller has more tools.

Words don’t make the story. My grandfather had an eighth-grade education. He had a very basic vocabulary. But man, listening to him tell a story was an experience I cannot describe.

Well, I’m going to try.

It was not the words he used at all; it was the way he spoke. He used inflection like a master working a clay pot. He had a grip on the dramatics. He knew when to sip.

Have you ever been listening to a story being told by a truly gifted storyteller, and he stops to take a sip of his drink? There is magic in that moment. The entire room freezes. No one speaks. No one breathes. The sounds of the room drop down to nothing. The TV in the background turns itself down, and everyone waits.

The thing I learned from my uncles, grandfather, and mother is that it is not the words, the sound effects, or even the tone of voice. It is in the pause. The pause holds all the power of the tale. Conversation is this way as well. Magical moments wait within the breath between words. The rhythm of the speaking tells the story in a way nothing else ever could.

Think about great orators. The breaths they take and the way they pause are the magic of the speech.

You don’t believe me. You are looking at me like you don’t believe me. Okay, let’s look at any piece of dialogue. I’m a writer. I happen to have some right on hand. Hold on while I get it.

Okay, I’m back. Did you notice that the period at the end of that last paragraph did not accurately convey the passage of time? Remember that. We are getting to that.

Now, in order to make my point, I’m going to show it to you bare bones and suck the illusion right out of the piece. Yes, my friend, there are illusions in every great piece of dialogue. That is actually why we are here. Just wait.

“I know, you make cheese. You’re a spy. Named Smear. Who makes cheese. Smear, the cheese maker. I would wager a guess that you’re the most dangerous cheese maker this country has ever known,” Rayph said.

“I’ll get better,” Smear said. Both laughed.

“I have to go. Got a thing to do. Thanks for the tea and what-have-you.”

This is the dialogue of a scene I have written. All the conversation is there. Every word of it. I have not changed a letter, not one piece of the conversation.

So, this is what we know now. Smear makes cheese. He is also a spy. He is dangerous and the country knows it. Rayph is leaving, and he has thanked Smear for the tea. We know that. It is right there. But the illusion of talking has been sucked out of it.

No one talks like this. This is totally unbelievable. Sadly, this is what I read a lot of the time. You can’t feel the cadence. You can’t feel the rhythm of the conversation. That is a major problem in writing because we are given crude tools to work with. We have a comma. That tiny piece of punctuation is supposed to imply a pause in the conversation. Well, it doesn’t. What would you say if I told you there is a long pause between the two phrases “thanks for the tea” and “what-have-you”? There is a pretty long pause there. Rayph also takes a breath for effect between the phrase “I know you make cheese” and the phrase “You’re a spy named Smear.” A pretty important pause lives right there. This conversation, like every one you have had, is riddled with pauses for effect and little breaths that give the dialogue meaning and make it worth listening to or reading.

In order to write real and convincing dialogue, we need to feel those pauses. They need to be there, but a simple comma or period will not do. It is too crude a tool. Go back up and read that piece of dialogue again. Feel how stilted it is and how clunky. Now, this is how it actually reads. This is the illusion I wove in it to give it breaths and dramatic pauses:

Rayph nodded. “I know, you make cheese,” Rayph said. “You’re a spy. Named Smear. Who makes cheese. Smear, the cheese maker. I would wager a guess that you’re the most dangerous cheese maker this country has ever known.”

“I’ll get better,” Smear said. Both laughed.

“I have to go. Got a thing to do,” Rayph said. He stood and drained his mug. “Thanks for the tea and,” he motioned to the cheese, “what-have-you.”

No comma in the world is going to change the first version into the second. But if we weave a little magic with tag placement, then we give the illusion of a pause. Look at the first line.

“I know, you make cheese,” Rayph said. “You’re a spy. Named Smear."

Placing “Rayph said” in the middle of the speech makes the reader pause to read that tag. The thing about tags is they are almost invisible. If you are reading a well-written piece, you don’t even notice them. They blow right by you. When you read that sentence, you don’t even think of the tag. But you have to pause in the conversation long enough to read it. That one beat, the amount of time it takes to read that two-word tag, gives the reader just enough of a breath to make it look like the speaker stopped talking for a moment, thought about what he would say, and said it.

One tag did that. It was not punctuation. It was not a really long period or comma that created the rhythm of the speech. It was a tag.

Let’s keep looking. I want to take a minute and look at the last part of the dialogue. Let’s start here:

“I have to go. Got a thing to do,” Rayph said. He stood and drained his mug. “Thanks for the tea and,” he motioned to the cheese, “what-have-you.”

I needed a longer pause between “Got a thing to do” and “Thanks for the tea.” So, I broke free of the conversation and, just for a breath, described an action. In the time it takes to read that tiny bit of description, the speaker has taken a long pause. I do the same thing between “Thanks for the tea and,” and the line “what-have-you.” In that breath, he has looked at the cheese and has been unwilling to call it cheese at all. He instead calls it what-have-you.

But when I throw in that line of Rayph motioning to the cheese, it gives the idea that he had no idea what to call it. Was it cheese or some other disgusting thing that he ate? Without a pause right there, a break in the rhythm of the conversation, we don’t understand at all.

Great dialogue, like a well-told story or a perfectly orated speech, is filled with pauses for dramatic effect. We can’t use those pauses when we write a conversation, but by using brief spots of description or a well-placed tag, we can create illusions of that same effect as if we were standing in the room hearing Rayph and Smear talk about tea and what-have-you.

Jesse Teller fell in love with fantasy when he was five years old and played his first game of Dungeons & Dragons. The game gave him the ability to create stories and characters from a young age. He started consuming fantasy in every form and, by nine, was obsessed with the genre. As a young adult, he knew he wanted to make his life about fantasy. From exploring the relationship between man and woman, to studying the qualities of a leader or a tyrant, Jesse Teller uses his stories and settings to study real-world themes and issues.

Connect with the Author

Welcome to another Friday Author Spotlight! This week I have Tiffany McDaniel with her debut novel, The Summer that Melted Everything. Tiffany shared a bit about herself in an interview, but first...

Welcome to another Friday Author Spotlight! This week I have Tiffany McDaniel with her debut novel, The Summer that Melted Everything. Tiffany shared a bit about herself in an interview, but first... Fielding Bliss has never forgotten the summer of 1984: the year a heat wave scorched Breathed, Ohio. The year he became friends with the devil.

Fielding Bliss has never forgotten the summer of 1984: the year a heat wave scorched Breathed, Ohio. The year he became friends with the devil.

Jesse Teller fell in love with fantasy when he was five years old and played his first game of Dungeons & Dragons. The game gave him the ability to create stories and characters from a young age. He started consuming fantasy in every form and, by nine, was obsessed with the genre. As a young adult, he knew he wanted to make his life about fantasy. From exploring the relationship between man and woman, to studying the qualities of a leader or a tyrant, Jesse Teller uses his stories and settings to study real-world themes and issues.

Jesse Teller fell in love with fantasy when he was five years old and played his first game of Dungeons & Dragons. The game gave him the ability to create stories and characters from a young age. He started consuming fantasy in every form and, by nine, was obsessed with the genre. As a young adult, he knew he wanted to make his life about fantasy. From exploring the relationship between man and woman, to studying the qualities of a leader or a tyrant, Jesse Teller uses his stories and settings to study real-world themes and issues.

Dimitri would like nothing more than to live a low-key life in Naples, Italy. His girlfriend, Syd, has other plans. After three months of researching, she is positive she has found a jinn on a killing spree in San Diego, California. Since Syd gave Dimitri the one thing he thought was out of reach, he feels obligated to use his ill-gained talents for her cause.

Dimitri would like nothing more than to live a low-key life in Naples, Italy. His girlfriend, Syd, has other plans. After three months of researching, she is positive she has found a jinn on a killing spree in San Diego, California. Since Syd gave Dimitri the one thing he thought was out of reach, he feels obligated to use his ill-gained talents for her cause.

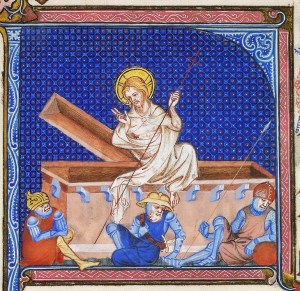

But on Easter morning, everything changed—Jesus had risen from the grave, and it was time for a celebration! Church began at sunrise, with everyone gathered outside of the church to sing hymns before going in for services. The darkness from before was replaced with light and the somber mood replaced by joy. Some monasteries put on plays to re-enact the day’s significance. The monks would wear white robes to represent the women who first discovered that Jesus’ tomb was empty, and that he was indeed risen. The forty day fast was finally over, and once all of the church-related activities had ended, it was it was finally time for feasting. Feasts were usually put on by royalty, lords, and wealthy nobles. Symbolically, putting on a great feast for the community was reminiscent of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. With no expense spared, it was an act of charity toward those who had much less, and whose winter reserves were nearing depletion (if not already depleted).

But on Easter morning, everything changed—Jesus had risen from the grave, and it was time for a celebration! Church began at sunrise, with everyone gathered outside of the church to sing hymns before going in for services. The darkness from before was replaced with light and the somber mood replaced by joy. Some monasteries put on plays to re-enact the day’s significance. The monks would wear white robes to represent the women who first discovered that Jesus’ tomb was empty, and that he was indeed risen. The forty day fast was finally over, and once all of the church-related activities had ended, it was it was finally time for feasting. Feasts were usually put on by royalty, lords, and wealthy nobles. Symbolically, putting on a great feast for the community was reminiscent of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. With no expense spared, it was an act of charity toward those who had much less, and whose winter reserves were nearing depletion (if not already depleted). Certain fun traditions were observed as well, such as wearing or receiving new clothes and enjoying colorful Easter eggs. Eggs were boiled in salt water to preserve them during Lent, when eating them was forbidden. They made their re-appearance on Easter, sometimes painted or dyed for the occasion—usually red to symbolize the blood of Christ. In Germanic regions they were painted green and hung on trees. Children made games of rolling them downhill, or they were hidden (and found) to represent the disciples finding Jesus’ empty tomb. Egg coloring could be as simple as boiling them with onions to give them a golden color, or they could actually be decorated with gold leaf, as Edward I did with his Easter eggs in 1290.

Certain fun traditions were observed as well, such as wearing or receiving new clothes and enjoying colorful Easter eggs. Eggs were boiled in salt water to preserve them during Lent, when eating them was forbidden. They made their re-appearance on Easter, sometimes painted or dyed for the occasion—usually red to symbolize the blood of Christ. In Germanic regions they were painted green and hung on trees. Children made games of rolling them downhill, or they were hidden (and found) to represent the disciples finding Jesus’ empty tomb. Egg coloring could be as simple as boiling them with onions to give them a golden color, or they could actually be decorated with gold leaf, as Edward I did with his Easter eggs in 1290.