Originally posted by Allison D. Reid:

Easter was the most important holiday in the medieval world, with many medieval calendars beginning the “new year” with Easter. The holiday included both serious reflection and joyous celebration. Lent was taken quite seriously—forty days of fasting was strictly observed, and the preparations made in anticipation of Easter were extensive. The days before Easter were largely spent in church, starting with the previous Wednesday when services called the Tenebrae began.

On Maundy Thursday (celebration of the Last Supper) the service was solemn and very quiet, with the altars stripped bare of all their decoration. Instead they were covered with branches. This was symbolic of the treatment Jesus received when he was stripped, beaten, and forced to wear a crown of thorns on his way to the cross.

On Good Friday, the medieval world mourned Christ’s death, and a common practice was to begin the day by “creeping to the Cross” barefoot and on one’s hands and knees. Church services were held in almost complete darkness, with just one candleholder (a Hearse) that was gradually extinguished to symbolize the earth falling into darkness. Only the central candle, which represented the light of Christ, remained lit. The priest would read the story of the Passion from the Gospel of John and lift up prayers for God’s mercy and the cleansing of their sins. It would have been a powerful ceremony. No one used tools or nails made of iron on Good Friday. Holy Saturday would have been another day of somber reflection as the world remained in darkness with Jesus lying in the tomb.

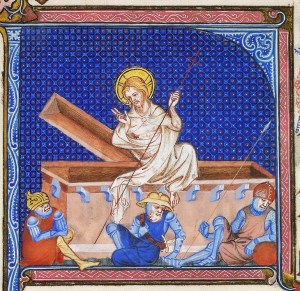

But on Easter morning, everything changed—Jesus had risen from the grave, and it was time for a celebration! Church began at sunrise, with everyone gathered outside of the church to sing hymns before going in for services. The darkness from before was replaced with light and the somber mood replaced by joy. Some monasteries put on plays to re-enact the day’s significance. The monks would wear white robes to represent the women who first discovered that Jesus’ tomb was empty, and that he was indeed risen. The forty day fast was finally over, and once all of the church-related activities had ended, it was it was finally time for feasting. Feasts were usually put on by royalty, lords, and wealthy nobles. Symbolically, putting on a great feast for the community was reminiscent of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. With no expense spared, it was an act of charity toward those who had much less, and whose winter reserves were nearing depletion (if not already depleted).

But on Easter morning, everything changed—Jesus had risen from the grave, and it was time for a celebration! Church began at sunrise, with everyone gathered outside of the church to sing hymns before going in for services. The darkness from before was replaced with light and the somber mood replaced by joy. Some monasteries put on plays to re-enact the day’s significance. The monks would wear white robes to represent the women who first discovered that Jesus’ tomb was empty, and that he was indeed risen. The forty day fast was finally over, and once all of the church-related activities had ended, it was it was finally time for feasting. Feasts were usually put on by royalty, lords, and wealthy nobles. Symbolically, putting on a great feast for the community was reminiscent of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. With no expense spared, it was an act of charity toward those who had much less, and whose winter reserves were nearing depletion (if not already depleted). Certain fun traditions were observed as well, such as wearing or receiving new clothes and enjoying colorful Easter eggs. Eggs were boiled in salt water to preserve them during Lent, when eating them was forbidden. They made their re-appearance on Easter, sometimes painted or dyed for the occasion—usually red to symbolize the blood of Christ. In Germanic regions they were painted green and hung on trees. Children made games of rolling them downhill, or they were hidden (and found) to represent the disciples finding Jesus’ empty tomb. Egg coloring could be as simple as boiling them with onions to give them a golden color, or they could actually be decorated with gold leaf, as Edward I did with his Easter eggs in 1290.

Certain fun traditions were observed as well, such as wearing or receiving new clothes and enjoying colorful Easter eggs. Eggs were boiled in salt water to preserve them during Lent, when eating them was forbidden. They made their re-appearance on Easter, sometimes painted or dyed for the occasion—usually red to symbolize the blood of Christ. In Germanic regions they were painted green and hung on trees. Children made games of rolling them downhill, or they were hidden (and found) to represent the disciples finding Jesus’ empty tomb. Egg coloring could be as simple as boiling them with onions to give them a golden color, or they could actually be decorated with gold leaf, as Edward I did with his Easter eggs in 1290.The celebration did not end on Easter Sunday, however. Hock Monday followed, during which young women “captured” young men and would only release them if paid a ransom (really a donation to the church). On Hock Tuesday, the roles were reversed and the young women were captured. As you can imagine, these antics did not always end well, and eventually attempts were made to better control them—sometimes even forbid them outright.

Use the Medieval Monday Index to discover more topics relating to daily life in the Middle Ages.

No comments:

Post a Comment